Why did I write this ‘big Franklin book?’

Early afternoon in Gjoa Haven, everyone gravitates to Qiqirtaq High School, a big modern building, for a cultural presentation. September 2017. I’m sailing in the Northwest Passage with Adventure Canada as a resource historian, giving talks as we travel. I’ve been rambling around Gjoa looking for Louie Kamookak, my old friend and fellow traveler.

As I take a seat on one of the tiered benches overlooking the gym, finally I spot him in a crowd of standees. He catches my eye and gestures toward the main entrance and we make our way into the hallway. After greeting each other, we fall to our usual kibbitzing. By now, age fifty-nine, Louie is widely recognized as the leading Inuit historian of his generation. We commiserate about not getting to meet each other, as planned, at the Erebus site.

He mentions speaking recently with a local Elder, interviewing him, and I say, “Wait, aren’t you an Elder yet? When are you going to become an Elder?”

New Answers to the Great Arctic Mystery

“I’m still too young,” he says, grinning. “Way too young.”

Then he comes back at me: “When are you going to write your big Franklin book?”

“My big Franklin book?”

“You’ve written about everybody else. Don’t you think it’s time?”

“No way.” I shake my head. “I’m still too young.”

Together we laugh.

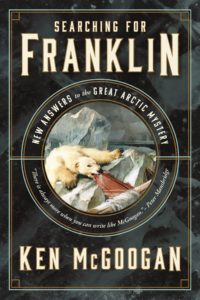

That was our last face-to-face meeting — Louie jokingly complaining that although I had published five books about Arctic exploration, I had yet to focus on the most famous northern explorer of them all: Sir John Franklin. I wrote this book to rectify that omission. Searching for Franklin – merely average in size, Louie, sorry! — challenges old orthodoxies, incorporates recent discoveries, and interweaves two main narratives.

The first treats the Royal Navy’s Arctic Overland expedition of 1819-22, during which Franklin rejected the advice of Dene and Metis leaders and lost 11 of his 20 men to exhaustion, starvation, and murder. The second discovers a startling new answer to that greatest of Arctic mysteries: what was the root cause of the catastrophe – history’s worst Arctic disaster — that engulfed the two-ship expedition on which Franklin embarked in 1845. What we see here is the front cover. Douglas & McIntyre will publish the book this autumn. Pub date: Oct. 7, 2023. More details soon!

Where can I get an autographed copy?

You’re on the list, Jay.

Looking forward to the book and to your RCGS talk on the 21st.

I’m rereading “Lady Franklin’s Revenge” in preparation for the newest edition. I hope Franklin does not replace John Rae as my hero. Looking forward to a new book.

Unless the book launch is north of 60, I want to be there, Ken. Here’s to another bestseller!

Never fear. That’s not going to happen.

Thanks, Ted. I still remember your great kindness and generosity when last we crossed paths.

Ken , I attended your noon talk today (6/21/23) with very great interest. and have written the following comments .

Both my husband and I are biologists. My husband has a background in parasitology and parasite immunology.

As I listened to you building your “case”, as soon as you referred to barrels of preserved bear meat, all my antennae were waving. After the presentation I immediately asked my husband: “Was it reasonable to suggest that trichina could have been transferred to crew members who ate inadequately cooked flesh of preserve bear meat and thence to crew who ate the flesh of dead infected crew members ?”. “Of course.”

But that lead to another question: What is the incidence of trichinosis among Inuit who lived in the area at the time ? Or even now ? Did they eat undercooked bear meat ? Or was there a related taboo? Or did the Inuit have some level of immunity from previously eating lightly infected bears over time ?

Obviously if any barrels of preserved meat are found on the vessels, it could be examined for trichina. But possibly immunological examination of any remains of crew might reveal trichina antibodies. Since it is unlikely immunological evidence could be found from long exposed bones, might there be unexposed remains of crew members still in either of the ships ?

If trichina are the culprit, then how was it that the men on the Victory essentially all survived possible trichina infection? Is there any evidence they didn’t eat any undercooked bear flesh ? Or did they aquire only very low doses that still allowed them to continue “normal “lives.

Since the Inuit ate mainly fish and sea mammals and often they let meat ferment prior to eating, did this help reduce the incidence of acquiring trichina from eating carnivore meat?

It seems at least that trichinosis can be added to the list of causes possibly contributing to the demise of Franklin’s crews.

. I hope to buy your book as soon as it is available

I note that both McGill and UBC seem to have more developed programs in parasite immunology

Looking forward to reading yor latest book!!!

Doreen, thanks for your keen interest. I am not a scientist. But I understand that, as you suggest, the Inuit did indeed develop a level of immunity down through the centuries . . . as European Caucasians did to certain diseases. As far as I recall, the men on the Victory never showed any symptoms. Ergo, probably they never ate infected bear meat. You’re right: the casks on the two ships might contain evidence. Also, as I understand it, any bodies (as opposed to skeletons) recovered. Finally, what about the three dead men on Beechey Island. Those bodies couldn’t disprove my “case,” but they could confirm it. Stay tuned!