Big Ideas

History is B-O-R-I-N-G. That’s the prevailing opinion.

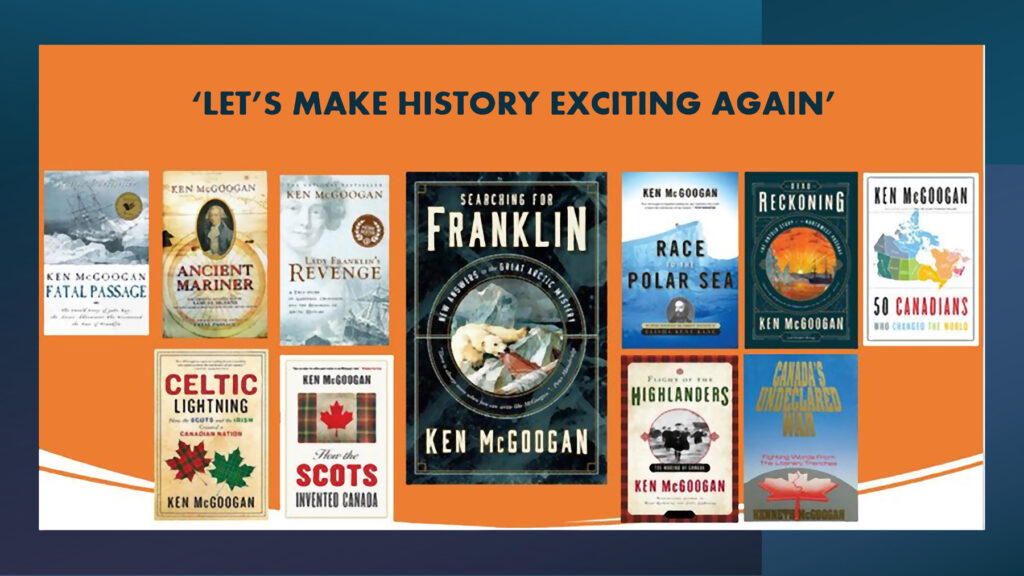

As an author who specializes in writing historical narrative, I find it problematic.

Part of the problem is that History has gone Academic.

Too many Professional Historians write History for each other. They have given up trying to reach a broad general audience and have turned History into the most conservative of literary genres.

The conventions are clear, the rules strict, the gatekeepers vigilant. If you write History, you write summary narrative in chronological order. And then and then and then. You write in a single authoritative voice. If you must spice things up, you can digress to present weighty exposition.

Okay, I exaggerate. But with History slipping further and further down any given curriculum, can we at least agree that something must be done?

As a writer, I control nothing but what and how I write. To get away from B-O-R-I-N-G, to reach a broad general audience, and to Make History Exciting Again, I suggest we take a Creative Nonfiction approach.

No, this does NOT mean making things up. It means “borrowing” narrative techniques from other genres -- novels, plays, movies – and applying them to writing History.

—Don’t be a slave to chronology. Flashbacks are just the beginning. Write a series of them using what I call The Rolling Now. Revisit Time’s Arrow by Martin Amis, Hopscotch by Julio Cortazar, Betrayal by Howard Pinter.

—Framing tales? Put your narrator in a box and set him or her free. The Tin Drum by Gunter Grass, Scann by Robert Harlow.

—Point of View? Shuffle cards like a magician, why not? The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing, The Alexandria Quartet by Lawrence Durrell.

—Point of View? Shuffle cards like a magician, why not? The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing, The Alexandria Quartet by Lawrence Durrell.

—Intertwine narratives: Pulp Fiction by Quentin Tarantino, Memento by Christopher Nolan. The list goes on.

—Some of these approaches have already been shown to work in nonfiction. See Being Geniuses Together by Robert McAlmon (revised by Kay Boyle) and The Wake by Linden MacIntyre.

Check out these approaches. Wave off the useless, the irrelevant. Adopt those techniques that serve your purpose. That, I think, is how we Make History Exciting Again.

In the autumn of 2016, as I write in Shadows of Tyranny, a wealthy American woman told me during a private conversation at a public event in Toronto that she was surprised to see Canadians taking such an interest in the US presidential election. We could not vote in it, after all. And presidents come and go every four years. Why would Canadians concern themselves?

I had expressed a worry that Donald Trump might get elected, and she was hinting that, as a Canadian, I should keep my opinions to myself. I observed mildly that whatever happened in the US affected the whole world and especially Canada. But then I let the matter drop. Canadian politesse, eh?

I was reminded of this incident not long ago when POLITICO magazine published an editorial under the headline: “Canada’s Big Worry: A US Civil War.” Alexander Burns, head of news, wrote that as political events unfold south of the border, we Canadians should stand quietly aside and “just watch.”

At the risk of sounding impolite, I have to say, well, that’s a non-starter. To be honest, I would suggest that Canadians worry less about a civil war erupting than about the Good Guys losing. Numerous brilliant Americans – among them Anne Applebaum, Robert Kagan, Timothy Snyder, Miles Taylor, Liz Cheney, Ruth Ben-Ghiat, Rachel Maddow — have written books warning that Donald Trump is threatening to turn the US into a fascist state. I believe them.

Urged to mind my own Canadian business, I flash back to Europe in the 1930s. Should the French and British — not to mention the Czechs, Poles, Norwegians, and Dutch — have kept their mouths shut while in Germany, the Nazis methodically seized control of Deutschland? And began furiously rearming while insisting, “Nothing to see here, folks, go on about your daily doings.” Britons like Winston Churchill, Americans like Dorothy Thompson and William Shirer, and Canadians like Matthew Halton sounded the alarm. Those in power declined to listen. Hadn’t Neville Chamberlain produced a piece of paper guaranteeing Peace in Our Time?

Obviously, I am not the first Canadian to draw attention to the evolving crisis in the US. Last year, Stephen Marche published The Next Civil War: Dispatches from the American Future. And early in 2022, the public intellectual Thomas Homer-Dixon warned Canadians that a storm was coming our way out of the United States. Writing in the “Globe and Mail,” Homer-Dixon drew attention to a dire portent: the Weimar Republic that governed Germany in the 1920s and early 1930s, and then gave way to the Third Reich of Adolf Hitler.

About such events, Canadians have a long history of rightly worrying. Forty years ago—incredible to think—novelist Margaret Atwood began warning of the rising threat of totalitarianism. As it happens, I interviewed her in 1985, when she published The Handmaid’s Tale. In a not-too-distant future, religious fanatics have turned much of the US into a patriarchal theocracy where some women, the so-called handmaids, are made to serve as sex slaves and baby-makers. “It’s an extrapolation of present trends set in the US,” Atwood told me. “There’s nothing in it that hasn’t actually happened somewhere. Polygamy? Check out the Mormon Church. Public hangings? They were standard in the 19th century.”

Many have insisted that you can’t use the past to predict the future. Fair enough. But I think of that old saw attributed most often to Mark Twain: “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” In the 1920s and early 1930s, some people did see fascism rising. Self-interested collaborators said yes to the totalitarian juggernaut, took to searching for scapegoats, and fanned the embers of anti-Semitism into a global conflagration.

But too many people remained blind until shamefully late in the day—among them Canadian prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, who after a face-to-face meeting with Adolf Hitler, declared him a latter-day Joan of Arc. Don’t believe me? Look it up.

The French did not start seriously mobilizing for war until September 1, 1939, after Germany invaded Poland and launched the Second World War. Early in May 1940, the Nazis bombed Dutch and Belgian airfields. They circumvented the vaunted Maginot Line and rolled over the French army. On June 14, motorcyclists led the invaders into Paris, so beginning the occupation of France by its powerful next-door neighbor—a subjugation that lasted four years.

No, I don’t anticipate an American invasion any time soon – despite the ramblings of Trump apologist Tucker Carlson, who in January 2023 wondered on Fox News why the US was “not sending an armed force north to liberate Canada from Trudeau.”

Given such precedent and context, and Trump’s well-documented admiration for dictators, how can anyone suggest that Canadians should stand silently and “just watch.” Remember the elephant and the mouse? Every twitch and grunt? As a Canadian, I politely decline to remain silent when my world, too, is threatened. I can only oppose, and loudly, anything that fosters the return of Donald J. Trump to the White House.

Six books, twenty-five years, more than a dozen Arctic voyages.

That’s what I needed to solve the Great Mystery: what happened to the Franklin Expedition of 1845? You know the story. Sir John Franklin sailed into the Arctic from the east, expecting to emerge into the Pacific trailing clouds of glory.

That’s what I needed to solve the Great Mystery: what happened to the Franklin Expedition of 1845? You know the story. Sir John Franklin sailed into the Arctic from the east, expecting to emerge into the Pacific trailing clouds of glory.

Instead, the expedition disappeared, losing 129 men and two state-of-the-art ships. Those vessels – Erebus and Terror – have been located beneath the waves in Canadian waters.

Since 2014 and 2016, underwater archaeologists from Parks Canada have been investigating, continuing a search for answers that has gone on for almost 180 years. The root cause of the catastrophe – the most bizarre in exploration history – remains a subject of contention.

But I do believe that, in Searching for Franklin: New Answers to the Great Arctic Mystery, I have solved the riddle.

In 1850, American explorer Elisha Kent Kane was among those who, on Beechey Island, found the graves of the first three men to die. Four years later, with the help of translator William Ouligbuck Jr., Orcadian John Rae gleaned from Inuit hunters that the final survivors of the expedition had been driven to cannibalism.

In 1859, Royal Navy captain Leopold McClintock reported the finding of the “Victory Point Record,” which indicated that 105 men had abandoned the two ships. In the 1860s and ’70s, Inuit interpreters led by Tookoolito and Ebierbing interviewed eyewitnesses and relayed details through expeditions led by the Americans Charles Francis Hall and Frederick Schwatka.

Questions multiplied. Why in 1848 did 105 men abandon the ships? Why were numerous men sequestered on shore in a massive hospital tent, where they died? Why did so many more officers than crewmen die early -- 37 per cent to 14 per cent?

Theories arose. Late in the 20th century, researchers pointed to lead poisoning, then botulism. But in the 2010s, leading scientists repudiated both speculations.

A turning point for me came when, while writing Dead Reckoning: The Untold Story of the Northwest Passage, I researched the 1619 Jens Munk disaster at Churchill. He arrived with 64 men and, after a single disastrous winter, sailed home with two. I unearthed a 1973 article by Delbert Young in which he argued – drawing on Munk’s journal -- that the root cause of that disaster was trichinosis. The men died miserable deaths because they ate infected polar bear meat that had been improperly cooked.

I investigated the Swedish North Pole expedition of 1897, learned that Dr. Ernst Tryde had written a book arguing that the three men involved died of trichinosis.

After further analysis, I brought my theory to Dr. David Waltner-Toews, one of Canada’s leading epidemiologists. His response? “It certainly looks like trichinosis.”

I have glossed over countless details, all of which I laid out in Searching for Franklin. Basically, I am arguing that the root cause of the Franklin catastrophe was trichinosis, complicated by scurvy and freezing cold. The men ate infected polar meat, began dying miserably, and abandoned the ships in panic. Cannibalism didn’t help.

In painting Man Proposes, God Disposes, Edwin Landseer got things right -- at least metaphorically. The polar bears did it!