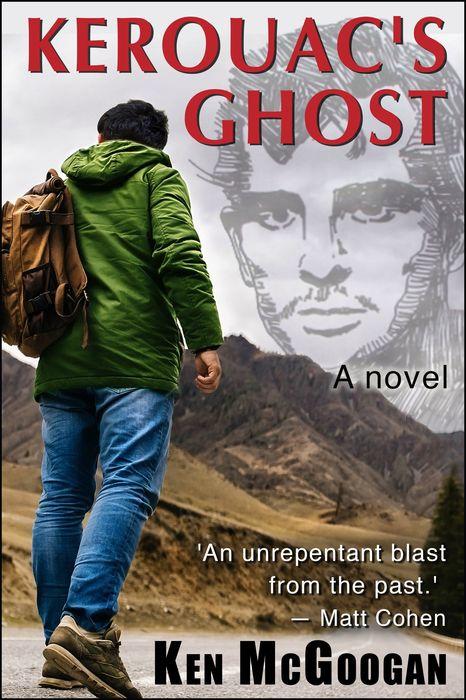

Kerouac’s Ghost: A Novel

Buy the Book: Amazon, Apple Books, Barnes & Noble, Indigo

Buy the Book: Amazon, Apple Books, Barnes & Noble, IndigoTitle: Kerouac's Ghost: A Novel

Published by: Bev Editions

Release Date: 2016

Overview

Frankie McCracken is still recovering from the Psychedelic Sixties when, while working as a fire lookout in the Canadian Rockies, he finds himself wrestling with a miracle-worker who claims to be the late Jack Kerouac, King of the Beats. This kaleidoscopic coming-of-age novel arrives in 2016 like a note in a bottle from a distant world. Fiction writer Matt Cohen hailed this work as "an unrepentant blast from the past." It juggles timelines and narrators, asserts that Kerouac was bigger than Beat, and celebrates his French-Canadian roots. This revised edition is the definitive version of a favorite novel. It inspired a song, also called Kerouac’s Ghost.

(VISIONS OF KEROUAC: Satori Magic Edition, Willow Avenue Books, 2008, Pottersfield Press, 1993; KEROUAC’S GHOST, Robert Davies Publishing, 1996. The novel was published in Quebec and France as LE FANTOME DE KEROUAC, Balzac-Le-Griot, 1998.)

From the 2016 Author’s Note:

In recent years, I have written mostly non-fiction. But early in my writing career, after completing an MFA at University of British Columbia, I published three novels. Kerouac’s Ghost is the only one I still like. It’s a first novel, a coming-of-age novel, a bit rough around the edges, but I find it playful and inventive and technically entertaining. Jacket copy describes it this way . . . .

Jack Kerouac, legendary King of the Beats, turns up raving in this kaleidoscopic novel about an obsessive survivor of the Psychedelic Sixties. Set mostly in the Haight-Ashbury District of San Francisco and atop Mount Jubilation in the Canadian Rockies, the narrative shuttles from Quebec to New York City, and from California into the Timeless Void of the Golden Eternity. It juggles time-lines and narrators, asserts that Jack Kerouac is BIGGER than Beat, and celebrates Great Walking Sainthood.

The novel is resolutely unfashionable. But it has survived several incarnations, and a couple of different titles, and it arrives like a message in a bottle from another world. Because the main story-line plunges us into 1966, this edition marks a 50th anniversary. I have revived the better title, Kerouac’s Ghost, and poked away at the Satori Magic Edition (introduced below).

For the rest, we have here A Novel of the Nineteen-Sixties, Psychedelic San Francisco, Dharma Bums in the Rockies, the Jungian Self, Too Much Drinking and Drugging, the Quebec-French Complication, Also Known as the Secret Canadian Life, and the Quest for Great Walking Sainthood.

Introduction to the 2007 Satori Magic Edition

The urge to resurrect this book seized me in 2005. I occasionally teach writing, and I had been preparing a workshop on Point of View. While casting about for examples to illustrate an argument, I thought of the two "Kerouac novels" I had published during the previous decade. Second time around, I had radically altered the Point of View. A cursory comparison of the two works proved unsettling, however, because I preferred the first version to the second—and I vaguely remembered having touted the latter as an improvement.

Luckily, I am good at repressing painful memories, and I quickly put this one behind me. The desire to resurrect went with it. But then, early in 2007, while sorting through paper-filled boxes in our basement, seeking to create a navigable passage, I came across a sheaf of papers and clippings pertaining to Jack Kerouac and those two novels. Flipping through them, again I found myself wishing that, back in the 1990s, I had made some different decisions.

The first version of the novel, Visions of Kerouac, had drawn a lot of encouraging reviews. Here was fiction writer Matt Cohen hailing the work as "an unrepentant blast from the blast, a politically incorrect celebration of men as libidinous explorers of the physical and spiritual unknown." And there was novelist Robert Harlow insisting that the book was "not just good, but very good indeed: in it you will find writing that has flair, headlong energy and the accessibility of a good letter home asking for money."

Several reviewers had drawn attention to the vitality of the work, among them Charles Mandel, who described Visions of Kerouac as "larger than life and crackling with energy . . . an exuberant celebration of the King Beat himself." Gerald Nicosia, author of Memory Babe: A Critical Biography of Jack Kerouac, had found another dimension worthy of note: "What I like best about Visions of Kerouac is the gentle voice of conscience underneath the adventure narrative, the writer who is not afraid to find his own heart and follow it amid a wilderness of souls who have lost their way . . . . McGoogan finds the trail to a new and saner life, both for himself and for those of us lucky enough to hear his words."

A couple of reviewers, obviously humorless, obtuse, insensitive types, disdained the novel's narrative antics as intrusive and "fashionably postmodern." But by 1995, the publisher, Pottersfield Press of Nova Scotia, had sold out almost the entire first edition. At that point, a Montreal publisher approached me suggesting that we republish the novel to reach a wider audience.

With exemplary generosity, Lesley Choyce at Pottersfield gave me back the publishing rights. I sat down to ferret out typos—and, to my surprise, found myself engaged in a rewrite. "I thought I was poking at a cadaver," I later told Quill & Quire magazine. "Suddenly it sat up and started making demands. I began thinking, 'Maybe I should do this? Maybe I should do that?’"

I blush to think of it now, but seized by the notion of reaching a mass audience, I strove to make the novel more accessible, and so more formally conventional. I eliminated two of the three narrators, dropped the framing tale involving the adult Frankie, and jettisoned arguments about the life and meaning of Jack Kerouac. I added a couple of scenes and tightened up language, but mainly, by confining the novel to a single Point of View, I said bon voyage to narrative hijinx, and to the playful exuberance that had distinguished the original.

Too late, as the debased rendition of the book, Kerouac's Ghost, was going to press, I received a note from literary critic David Staines, responding to the original work: "It is a fine, wild, wonderful, engrossing novel, and I enjoyed every minute of it. It should have been nominated for the Smith Books First Novel Award." Staines went on: "I was moved by the novel, haunted by the figure of Frankie and the relationship with the parents, especially the father."

Staines was taken with the evocation of San Francisco, a city he knew only slightly, but: "Above all, I became involved in the story, in the flashbacks and flash-forwards, in the small Quebec town, in the Montreal I too know, and in the Quebec City conference."

Alas, that Quebec City conference, which dramatized clashing responses to the real-life Kerouac, had ended up on the cutting-room floor. The new book, which appeared in 1996, inspired a promotional trip to California. It was translated into French as Le Fantome de Kerouac and drew positive notices en francais—but it reached no mass audience in either language.

Meanwhile, novelist Harlow had raised a red flag. He had dipped into the revised work, he wrote, but: "I had— still have—trouble getting around why, and for what gain, you did the book over. It was good the first time." I think he meant "better the first time" but did not have the heart to say so.

Novelist Ann Ireland felt no such qualms. The core of the original work, she wrote in Quill & Quire, "is Frankie's own road tale, full of comic scenes, misadventures, and speculations on the nature of Kerouac's gift. Was he truly the King of the Beats? Did alcoholism cause the disintegration of his talent? And how important was his French-Canadian background? Most of all, it is about the obsession Frankie McCracken feels for his mentor, how he acts on it, and finds himself fusing with Kerouac's spirit-self."

In the revised work, Ireland rightly observed, because the framing tale is gone, "we never see Frankie as a mature man, looking back at his young, naive self." The single Point of View, with the ghost of Kerouac narrating the entire novel, also introduces credibility problems: "why would Kerouac be obsessed with this young Seeker who flees his small town to find out about himself and the world."

The ghost is driven by his quest for Great Walking Sainthood. Yet Ireland was right to suggest, “Where the first novel was, to a large extent, a dialogue with the self about Kerouac and the meaning of his work and life, this second is much more focused on Frankie's spiritual awakening." By eliminating the clashing interpretations of Kerouac, the revised novel "underlines the spiritual theme with a heavier hand." Ultimately, Ireland wrote, "Visions of Kerouac felt, in its less disciplined and more rambunctious way, more imbued with the Beat spirit."

In 1996, when this perceptive analysis appeared, I ground my teeth and dismissed it. I kept writing, published two more novels into oblivion, and then, with a book called Fatal Passage, turned mainly to narrative nonfiction. I did notice when another novelist scored a critical success by borrowing the interrogative voice from Visions of Kerouac (I myself had taken it from James Joyce). And I reflected fleetingly that the simpler Kerouac's Ghost would never spawn any such emulation.

Still, I let go of the agonizing. And the days ran away like wild horses over the hills, as Charles Bukowski once observed. They kept right on running until early in 2007, when in our over-crowded basement I rediscovered the responses of Harlow, Ireland and Staines. Turning to the novels themselves, I realized that, in radically revising the book, I had reduced vitality, resonance, dimension, and possibly even literary significance. Despite its flaws and gaucheries, the first version, Visions of Kerouac, was by far the better book.

Of course, it is just a first novel. As such, it had a long gestation period. I see the book now as a message from a world that has long since disappeared—a world without bank machines and cell phones and above all without the Internet, and in which you would send off a letter and expect to wait two or three weeks for a reply.

A note in a bottle, then. But as I awakened to this during that great sorting and shifting in the basement, I realized, too, that any future readers would naturally approach the second, inferior version of the novel believing it to be the one I wished to preserve. And with that I stopped fretting about what I had done and began asking, "What can I do?"

The answer you hold in your hands, thanks largely to yet another change in communications technology, the advent of Print On Demand publishing. For the past couple of years, while leading workshops on How to Survive as a Writer (an admittedly dubious proposition), I have been arguing that the best use of POD, at least in the early 21st century, is to revive out-of-print books—works that arrive wearing at least a fig leaf of credibility as a result of having survived the editorial process.

And when, in our basement, this suddenly occurred to me, I jumped to my feet and shazaam! had a full-blown satori, a razzle-dazzle, knock-'em-onto-the-floor-style awakening on a scale that Kerouac himself would have approved. It is also possible that I smacked my head on a low-hanging joist. Either way, this time around, having told that talkative cadaver to sit down and shut up, I have confined myself to making just a single macroscosmic change. In the original novel, whenever I shifted narrators, I altered typefaces. In this Satori Magic Edition, I have identified the narrator at the beginning of each chapter.

Beyond that, I have corrected typos, poked at the language and, all right, I admit it, made a few minor revisions. Bottom line: this is officially IT—the definitive, irrevocable, ultimate, ineluctable and incontrovertibly final version of my first published novel. . . . . [Later, as we have seen, I changed my mind and took one more crack at revising the book.]