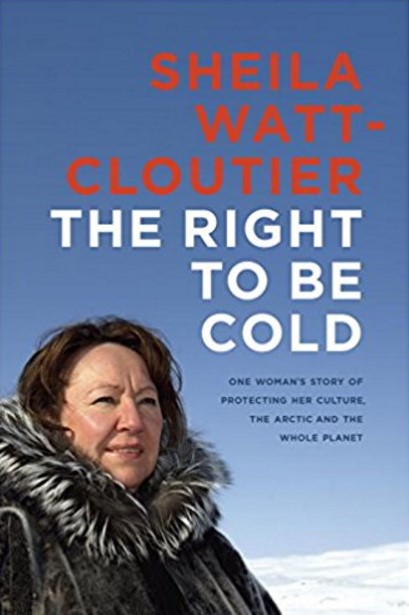

Meet the Inuit activist who made climate change a human rights issue

In December 2005, Inuit author and activist Sheila

Watt-Cloutier launched the world’s first legal action on climate change when

she presented a 167-page petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human

Rights. Signed by sixty-two Inuit elders and hunters, it charged that unchecked

emission of greenhouse gases from the United States had violated Inuit cultural

and environmental rights as guaranteed by the American Declaration of the

Rights and Duties of Man.

Watt-Cloutier changed the world by making climate

change a human rights issue. So I argued, rightly I think, in 50 Canadians Who Changed the World. I

had organized my Outstanding 50, all born in the twentieth century, into six

broadly inclusive groups. Watt-Cloutier I profiled as primarily an activist. In

presenting the petition, she drew on an

exhaustive Arctic Climate Impact

Assessment (ACIA) prepared over four years by 300 scientists from fifteen

countries. It attested that the Arctic is experiencing some of the most rapid

climate change on earth. It predicted that the change would accelerate and

produce major physical, ecological, social, and economic consequences, and that

these would lead to worldwide global warming and rising sea levels. Some marine

species would face extinction, and the disappearance of sea ice would disrupt

and might destroy the Inuit’s hunting- and food-sharing culture.

Identifying

the Inuit as “the early warning system for the entire planet,” Watt-Cloutier

put a human face on the facts, figures, and graphs. “Climate change affects

every facet of Inuit life,” she said. “We have a right to life, health,

security, land use, subsistence and culture. These issues are the real politics

of climate change.” In 2008, when Time

magazine hailed her as one of a handful of “Heroes of the Environment,”

Watt-Cloutier said: “Most people can’t relate to the science, to the economics,

and to the technical aspects of climate change. But they can certainly connect

to the human aspect.” Her aim is to “move the issue from the head to the

heart.”

The following year, while accepting an honorary

doctor of laws from the University of Alberta, Watt-Cloutier reviewed how the

Inuit “have weathered the storm of modernization remarkably well, moving from

an almost entirely traditional way of life to adopting ‘modern’ innovations all

within the past sixty or seventy years.” But rapid changes and traumas “deeply

wounded and dispirited many,” she said, “and translated into a ‘collective

pain’ for families and communities. Substance abuse, health problems, and the

loss of so many of our people to suicide have resulted.”

Through all this, the Inuit drew strength from “our

land, our predictable environment and climate, and the wisdom our hunters and

elders gained over millennia to help us adapt.” Now, however, climate change

has made the environment unreliable and capricious: “Just as we start to come

out the other side of the first wave of tumultuous change, there is yet a

second wave coming at us. We face dangerously unpredictable weather, unpredictable

conditions of our ice and snow, extreme erosion, and an invasion of new

species. These changes threaten to erase the memory of who we are, where we

have come from, and all that we wish to be.”

Writing in 2012, I added a lot more. But obviously, I

could not include anything from The Right

to be Cold, a national bestseller Watt-Cloutier published in 2015. Seems to me that, along with 50

Canadians, we all should have that book on our bedside tables.

Must check that out.