First review hails “rewrite of Arctic history”

Here comes Searching for Franklin

By Dave Obee

Editor/Publisher

Victoria Times-Colonist

Sir John Franklin has been one of the most controversial, and misunderstood, figures in the history of exploration of Canada’s north.

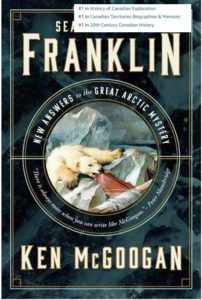

In this book, Ken McGoogan provides a fresh look at what made Franklin tick – and the factors that caused him to send so many men to early graves.

Searching for Franklin is nothing short of a rewrite of Arctic history. McGoogan takes us well beyond the common narrative, and offers insight into the reasons why Franklin could not understand the risks he was taking by ignoring the advice of others.

Franklin’s ill-fated expedition in search of the Northwest Passage became legendary, for all the wrong reasons. For one thing, the expedition failed, and everyone involved died.

That didn’t stop Franklin’s widow from declaring the expedition a rousing success and sponsoring seven expeditions in an effort to find out what had happened to her husband’s two ships, the Erebus and the Terror.

Her strong defence of her husband has not worn well; we have learned too much about what happened. For almost two centuries, Franklin’s failed expedition has cast a dark shadow over the history of the Northwest Passage.

The 1987 publication of Frozen in Time, dealing with the exhumation of three graves of Franklin Expedition crew members, brought renewed public interest to the disaster with its theory that lead poisoning should be blamed for the mass deaths.

Searching for Franklin is the 16th book by McGoogan, and his sixth on Arctic exploration. One of his previous books dealt with Lady Franklin’s efforts to establish her husband’s reputation.

McGoogan’s latest book goes well beyond Franklin’s final journey, including a comprehensive report on his overland expedition in 1819-1822 that was also a miserable failure.

It is striking that Franklin learned nothing from that failure; if anything, it seemed to boost his confidence, and his belief that he did not need to listen to those around him.

McGoogan argues that Franklin’s strong religious beliefs prevented him from seeking help, or accepting advice when it was offered.

For whatever reason, Franklin was not the only explorer to reject the wisdom of the people who knew the most about the areas they were in — the people who lived there.

The Inuit knew how to stay alive in the cold, treeless north. They knew the routes to travel from one spot to another. They could have helped Franklin and the rest, but their advice went unheeded.

After the Erebus and Terror went missing, the Inuit in the area could have helped those who went in search of Franklin and his men. They had seen some of the surviving members of the expedition, and had found items that had been on the two ships.

They could have helped. They could have made a tremendous difference, and made northern discoveries easier. They could have reduced the number of people who died in the quest for the Northwest Passage.

But they were not asked.

In Searching for Franklin, McGoogan includes reminiscences of his own journeys to the Arctic and the remarkable people he met there as he sought information on explorers.

McGoogan gives his friend Louie Kamookak special credit for inspiring this book, one that he challenged McGoogan to write.

We owe thanks to Kamookak for that — and, of course, to McGoogan. Searching for Franklin introduces us to the man behind the myth, and it’s about time.

Franklin lost half his men to starvation or, to be kind, questionable circumstances. There were allegations of murder and cannibalism. Franklin became known as “the man who ate his boots” – and yet, on his return to England, he was hailed as a hero.

Franklin lost half his men to starvation or, to be kind, questionable circumstances. There were allegations of murder and cannibalism. Franklin became known as “the man who ate his boots” – and yet, on his return to England, he was hailed as a hero.