Marvelling at the legacy of Farley Mowat

Our Hero writes in the National Post . . .

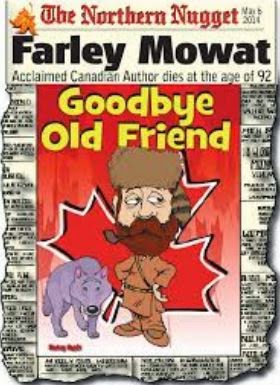

The recent death of Farley Mowat

at 92 sparked heartfelt reminiscences and stirred up old controversies. But the

most interesting question, going forward, concerns legacy. Some of us contend

that Mowat was a giant. For starters, we cite numbers: 45 books, 60 countries, and

(ballpark) 15 million

copies sold. But if, as a writer, Mowat was a Gulliver in

Lilliput, and not just commercially, then surely he left a legacy? He must have

established or advanced some literary tradition? Profoundly influenced younger Canadian

writers?

The answer is an emphatic yes.

Born May 12, 1921, Mowat energized not only the Baby Boomers, my own

generation, but younger writers. Before going further, a clarification: as a

Canadian, Mowat is often linked with Pierre Berton, who was born ten months before

him. Both were prolific, larger-than-life personalities published by Jack

McClelland. Both wrote mainly nonfiction.

But Berton, who cut his

professional teeth as a journalist, became famous for sweeping Canadian

histories: The National Dream, The

Invasion of Canada, Vimy, The Great Depression, The Arctic Grail.

Contemporary Canadian historians who achieve readability while tackling big

themes are working in a tradition established by Berton and Peter C. Newman (The Canadian Establishment, Company of

Adventurers). Think of Margaret Macmillan and Paris, 1919, or of Christopher Moore and 1867: How the Fathers Made a Deal. Think of such military

historians as Tim Cook, Mark Zuelke, and Ted Barris.

Farley Mowat did not write

history. He took a keen interest in prehistory, in archaeology and legend, and

so produced West-Viking and The Farfarers. But looking back at his

long career in context, we discover that Mowat was Canada’s first writer of

creative nonfiction (CNF). . . .

TO READ THE REST, CLICK HERE AND GO TO THE NATIONAL POST.