Chasing the Irish Pirate Queen around the Aran Islands

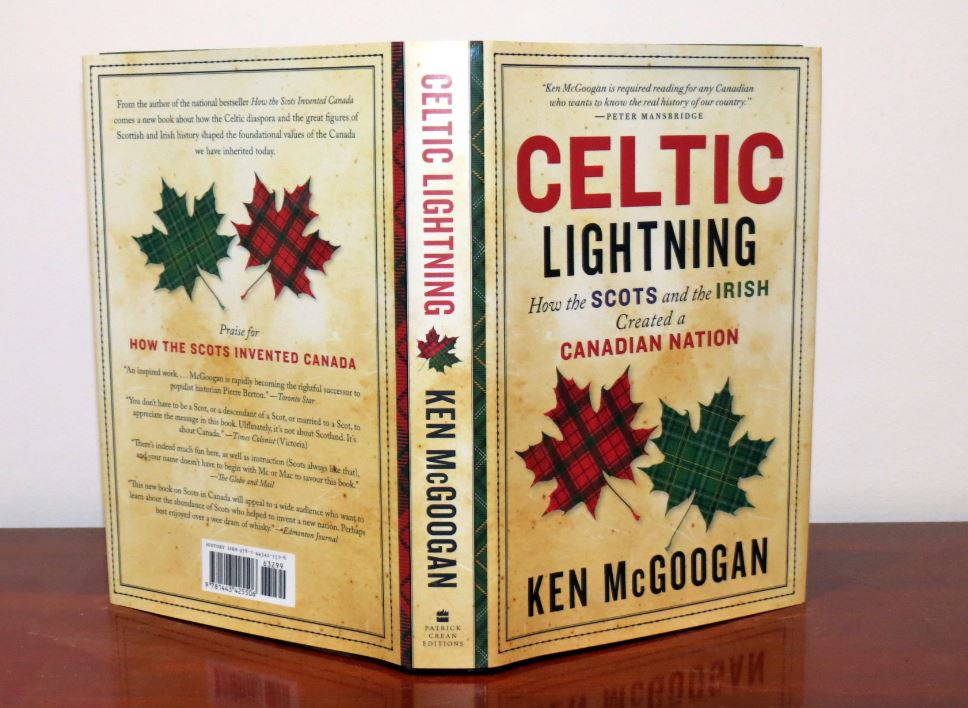

Hats off to James McQuiston, editor and publisher of The Celtic Guide, a superbly professional magazine that reflects his passionate interest in Scotland and Ireland. The December issue (click here) features contributions from throughout the Celtic world. They include an excerpt from my latest book, Celtic Lightning: How the Scots and the Irish Created a Canadian Nation, which has just appeared in paperback (HarperCollins Canada). That excerpt begins as follows . . . .

Off the south coast of Ireland, in choppy seas,

Off the south coast of Ireland, in choppy seas,

we sailed around Skellig Michael, a rocky island that rises, volcano-like,

seven hundred feet into the air. We marvelled to think that, for centuries,

Christian monks lived in beehive meditation huts near the top, and would reach

them in the wind by clambering out of their coracles and climbing six hundred

stone steps, narrow, steep, and often wet. We were circumnavigating Ireland

with Adventure Canada, Sheena and I, going ashore once or twice a day in

Zodiacs. Off the west coast, on Inishmore in the Aran Islands, where children

learn Gaelic as their first language, we debarked and followed a rugged

footpath uphill to Dun Aengus, a ritual site from the Bronze Age. Here one of

us determined that, yes, we could terrify ourselves by lying on our stomachs,

crawling to the edge, and looking straight down to where, a hundred metres

below, white waves smashed into the black rock face.

But the most evocative moment of the

circumnavigation of Ireland came on Inishbofin, which is located north up the

west coast, off Connemara. As we rode from our ship to the dock at Inishbofin,

eight or nine people to a Zodiac, we passed Dun Grainne, the remains of a fortress used in the 1500s by the

legendary Pirate Queen “Grainne” or Grace O’Malley. Born into a powerful

west-coast family, O’Malley rejected the traditional roles available to

females. She became a skilled sailor, gained control of a merchant fleet, and

conducted trade as far away as Africa. Her enemies denounced her as “the most

notorious sea captain in Ireland,” and complained that she “overstepped the

part of womanhood.”

The Celtic tradition that produced

O’Malley—that of the dauntless woman, latterly known as feminism—has never been

short of exemplars. Besides the Irish Pirate Queen and the Scottish Flora

MacDonald, saviour of Bonnie Prince Charlie, there was Maria Edgeworth, who has

been called the Irish Jane Austen. She kicked down doors through the early

1800s. And later that century, after seeing Irish tenants evicted from their

lands, the activist-actress Maud Gonne inspired William Butler Yeats and

thousands of Irish nationalists.

In Scotland, the first

champion of Scottish independence to be elected to the British House of Commons

was a woman, Winifred Ewing, leader of the Scottish National Party. Five years

later, in 1972, and in that same hallowed house, a twenty-year-old Irish MP,

Bernadette Devlin, delivered “a slap heard round the world” when the Home

Secretary claimed that on Bloody Sunday, British troops had shot more than two

dozen unarmed protestors in self-defence. Having witnessed the massacre – 13

died that day, and one later — Devlin crossed the floor and slapped his face.

In this unbroken Celtic

tradition of “overstepping women,” which extends backwards to Saint Brigid of

Kildare (451–525) and forward to its flowering in the contemporary world, Grace

O’Malley came early. In June of 1593, as she sailed up the River Thames to meet

Queen Elizabeth I, she would have known little about what her privateering

English counterparts were doing. Walter Raleigh was organizing an expedition to

discover the Lost City of Gold in South America. Martin Frobisher, having

conducted three expeditions to North America, was plundering ships off the

coasts of France and Spain. Francis Drake, circumnavigator of the world, was

ranging around North Africa, the Caribbean, and South America, seizing booty

wherever he found it.

Grace O’Malley, commander of a fleet of galleys

and several hundred sailors, had sailed from the west coast of Ireland to seek

the removal of the ruthless Richard Bingham, the English-appointed governor of

Connaught. Bingham was the one who had denounced her as “a woman who

overstepped the part of womanhood,” and labelled her “the most notorious sea

captain in Ireland.” She sought the release from Bingham’s jail of a

half-brother and of her son, Tibbot. Also, she hoped to secure the right to

maintain herself “by land and sea,” by which she meant forcibly collecting

“tax” from any ships that plied the waters she patrolled. The merchants of

Galway were allowed to do this: why was she prevented?

To read the rest click here . . . and then pick up a copy of the book, available in better bookstores everywhere. (Pix above by Sheena Fraser McGoogan.)