How Irish Coffin Ships changed Canada

An excellent article in the June/July issue of Canada’s History magazine, written by Don Cummer, tells the story of how in the 1840s thousands of Irish refugees fled the Great Hunger for a new life in Canada. It brought back memories of how in 2019 I spent a couple of months ranging around Ireland while exploring the many dimensions of the Irish famine. I wrote about it in the December 2019 issue of Celtic Life International. It’s not all that far to Tipperary, I declared in Part Two of a three-part series — not if you start in Kilkenny and make for the Famine Warhouse at the eastern edge of that song-famous county. We simply drove west for about 30 km, which included a short detour because we took a wrong turn and ended up exploring a one-lane road with a ridge of grass down the middle.

An excellent article in the June/July issue of Canada’s History magazine, written by Don Cummer, tells the story of how in the 1840s thousands of Irish refugees fled the Great Hunger for a new life in Canada. It brought back memories of how in 2019 I spent a couple of months ranging around Ireland while exploring the many dimensions of the Irish famine. I wrote about it in the December 2019 issue of Celtic Life International. It’s not all that far to Tipperary, I declared in Part Two of a three-part series — not if you start in Kilkenny and make for the Famine Warhouse at the eastern edge of that song-famous county. We simply drove west for about 30 km, which included a short detour because we took a wrong turn and ended up exploring a one-lane road with a ridge of grass down the middle.

The Famine Warhouse is the site of an 1848 incident known as the Battle of Widow McCormack’s Cabbage Patch – an episode that to me represented a fourth and final dimension of the Great Famine. By this time, three weeks into our latest Irish ramble, and somewhat to my surprise, I had come face to face with the politics, the science, and the human suffering of the Great Hunger. I saw the Warhouse as symbolizing the active response – the rebellion. But I have gotten ahead of our wanderings around southeastern Ireland, an area that, during the famine years, fared relatively well. Hence my surprise. . . .

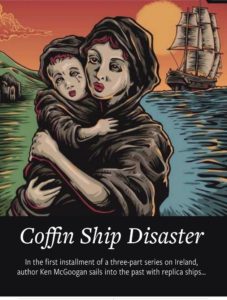

In Part One of the series, which turned up in the October issue, I wrote of the so-called Coffin Ships. In June 2018, I noted, scientists confirmed the identification of the human remains found on the beach at Cap des Rosiers, Quebec. They had come from the 1847 shipwreck of the Carricks of Whitehaven, a famine ship that had sailed from Sligo on the west coast of Ireland. Bound for Quebec City, the two-masted vessel had been approaching the mouth of the St. Lawrence when on April 28 a fierce storm came up, drove the wooden ship onto a shoal, and smashed her to pieces.

Now, more than 200 years later, Parks Canada anthropologists confirmed that the remains – bones and skeletons uncovered by storms mostly in 2011 and 2016 – were indeed those of Irish men, women and children who had sailed on the Carricks during the Great Famine in its worst year.

Now, more than 200 years later, Parks Canada anthropologists confirmed that the remains – bones and skeletons uncovered by storms mostly in 2011 and 2016 – were indeed those of Irish men, women and children who had sailed on the Carricks during the Great Famine in its worst year.

As I tracked the story from my home in Toronto, I could imagine the terrible demise of those last survivors all too vividly. Less than one month before the story surfaced, I had gone aboard two replica famine ships in Ireland – the Jeanie Johnston in Dublin and the Dunbrody in New Ross, County Wexford. And in 2018, in Pictou, Nova Scotia, I had explored the replica of the Hector, which famously sailed from Scotland in 1773, decades before Thomas D’Arcy McGee coined the term “coffin ship.” In size and eight, the 200-ton Hector was closest to the 242-ton Carricks. . . .

The preceding May, in this very blog, I wrote: The terrible parallels hit you like a bucket of cold water in the face — at least if you have been immersed for a while in Scotland’s Highland Clearances. Check out the image above. Looks like it could be from a Scottish Clearance in Sutherland or Glengarry, or perhaps Lewis, Uist or Barra. In fact, it’s from County Clare in Ireland — Mathia Magrath’s house “after destruction by the Battering Ram.” I know this because today we checked out the Irish Famine Exhibition at St. Stephen’s Green Shopping Centre in Dublin.

The exhibition, which runs until Oct. 15, brought the famine experience front and centre for me. Between 1845 and 1851, approximately one million Irish people died of starvation or disease and a couple of million emigrated, many of them to Canada. Many of those were forcibly evicted by landlords spouting the free-market doctrine of laissez faire. The end result: an Irish diaspora that has produced a globe-scattering of something like 70 million people of Irish descent. The decades immediately after the famine brought mostly silence about that trauma. More recently, scholars and others have turned increasingly to the Great Hunger, as it is also called. . . . Anyway, if after checking the links in this post you yearn to know more, I say pick up the latest issue of Canada’s History. Cummer’s article comes with vivid illustrations.

McGibbons were my Clan – I think they settled in Labelle Quebec

At Ellis Island a few years ago, we were told that immigrants not accepted into the US had to be transported back to their original port of embarkation – at the shipping companies’ expense. This rule was to incentivize shippers to exercise some judgement over who they agreed to transport to America.

The apparent difference vs. Canada is striking. Is the story we heard at Ellis Island story true Complete? Did Canada not have similar requirements? Did rules come into effect at different times? For example, did the US rule above not apply until Ellis Island opened in 1892?

(My great grandfather emigrated from County Sligo to the US in 1850, impoverished and likely illiterate. I thought that must have been extremely difficult. But I never before knew anything of the Irish experience immigrating to Canada.)

Hi, John. I don’t believe that Canada had any such requirement. And sorry, but I am not familiar with the Ellis Island regulations. Interesting question, I agree.