BC Review celebrates Big Franklin Book

And the excellent reviews keep coming. Gotta love this one for reflecting my methodology!

BRITISH COLUMBIA REVIEW

BY RON VERZUH / Jan. 4, 2024

Ken and Louie at the John Rae cairn, 1999

In the early 1970s, I joined an aerial search for three sports fishers lost somewhere in the vast tundra of the Northwest Territories. A German-born bush pilot named Marten Hartwell had recently made international headlines when he crashed his plane and purportedly survived by eating a dead passenger. Shocking, yes, but it wasn’t the first time such incidents had occurred in the far north. Ken McGoogan refreshes our memory about one historic instance in Searching for Franklin.

Other than the location, endless stretches of wilderness marked by the odd caribou herd, my search had nothing in common with British explorer Sir John Franklin’s three unsuccessful attempts to find the coveted Northwest Passage to Asia in the 1830s and again in the mid-1840s. It was a challenge that had gone on for centuries before him.

In most ways our search was a comparative luxury. Our team of volunteer “spotters” was tucked cozily into the modified back end of a huge Hercules Air Force Transport. The job was to watch the snowy ground one half-hour at a time, looking for signs of a crash. The other half we slept exhausted from the intense focus needed for the task.

There were few luxuries for the men who signed on to Franklin’s ill-fated journeys into Canada’s rugged NWT (then part of Rupert’s Land). One of the most interesting parts of McGoogan’s account is his portrait of these rugged workers, men who needed to eat boiled shoe leather and tripe de roche (lichen) to sustain themselves in the brutal climate.

Pemmican, the dried mix of meat and fat favoured by Metis and French Canadian voyageurs, was perhaps the only luxury and only when wild game were scarce. When they were plentiful, the men would ravenously devour kills of muskox, deer, caribou, and bear. In hard times, the bones served as their meals. McGoogan provides intricate details of the hunts and the feedings.

Franklin, a vain and evangelically religious man, then returned from a stint governing an Australian penal colony, was looking for glory and a sizeable purse of more than $1 million if the elusive passage was found. An earlier set of explorers had provided charts that supposedly led to a channel to the Pacific Ocean to facilitate lucrative trade with the Orient.

“How hard could it be?” asked McGoogan sarcastically. The historian interjects himself through much of this narrative of misadventure, bravery, and blind ignorance on Franklin’s part. As he notes, Franklin dismissed the local knowledge of leaders like Akaitcho of the Dene (Yellowknife) First Nation. And yet he was reliant on that knowledge and experience.

Sir John also arrogantly disregarded advice from interpreters, hunters, and fishers about expedition preparedness and the timing of travel. Without the local workers, Franklin was lost but he put his faith in his Christian God rather than give an inch to the heathen wretches who could have been his salvation. He was “a true believer, who could preach but could not listen.”

McGoogan takes us with him on his own travels of discovery in the north. He has written numerous books based on them. He also introduces us to his long-time travelling companion Louie Kamookak, a specialist in Inuit oral history. In dialogue with his friend, the historian traces some of the many searches for the lost expedition. It adds a personal note to this tragic tale marked by hubris, pride, and British military stubbornness.

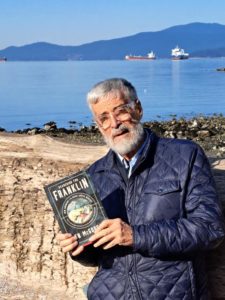

The Big Franklin Book at the Pacific Ocean

Franklin made three voyages in the Arctic, but the story about two ships, the HMS Erebus and the HMS Terror, stuck in the ice and abandoned by the 128 crew, has perhaps most captivated arctic explorers and writers. To this day, theories abound as to their plight. Lady Franklin, the explorer’s proud spouse, spent years and millions encouraging searches. At one point, she even commissioned British novelist Charles Dickens to deflate rumours that Franklin had resorted to cannibalism to survive.

McGoogan reveals that such deeds, along with murder and madness were all part of the expedition. Near frozen, beaten by the northern climate, and lost much of the time, the officers and crew of the Franklin and earlier expeditions were forced to unspeakable acts. Even a duel was threatened over a First Nations woman named Greenstockings.

McGoogan has done an excellent job of dropping us into the time and place of “the greatest catastrophe in the history of polar exploration.” But it still is hard to imagine the pain and suffering that these men endured. Why they followed the ego-driven Captain Franklin to their deaths will remain open to speculation.

In the end, the whole business might seem a somewhat wasted and costly exercise. It took another 50 years until Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen found the Northwest Passage through the Arctic archipelago in 1905. Still, fame and fortune had been made and lost in the intervening years of futile searching.

Many historians have offered theories about how the expedition members died. McGoogan suggests the culprit was the polar bear. No, not that they were eaten by bears, but that they ate bear meat filled with poisonous trichinosis. It’s as good a theory as any and the historian is persuasive.

As McGoogan stresses, the heroes of this story are not the British explorers and least of all not John Franklin. They are the indigenous trappers, crack-shot hunters, guides, and interpreters. They were the voyageurs at the Hudson’s Bay Company and rival North West Company who provisioned the explorers, offered guidance, and sometimes rescued them. These are the unsung people who did the heavy lifting while Franklin enjoyed the relative luxuries of his station.

Historians have picked at the bones of the Franklin story ever since the tragic events took place in the mid-1840s, but no

one has uncovered the full truth of why the expedition went wrong. Now, McGoogan points the way to understanding how “Franklin disappeared into the white booming emptiness with two ships and 128 men, never to be seen again.” We know that Franklin died on June 11, 1847. Several of his men died the next year, trying to save their lives after trying to save his.

Writer Pierre Berton called him a “quite ordinary naval officer.” Novelist Margaret Atwood called him “a dope.” McGoogan argues that he was “a well-meaning plodder” and he has done his best to shape the story as part history and part personal discovery. From my reading, however, so much money and life were spent looking for a man who really didn’t do much of great historical value . . . except get irretrievably lost.

***

At the end of eight hours of spotting in the Hercules, like those searching for Franklin we failed to find the lost fishers. A few days later the CBC announced that the search had ended. The downed plane had been found way off course on the Beaufort Sea. The fishers got lost but were safe. The taxpayer was out of pocket several hundred thousand dollars. Another fruitless adventure, but happily no fatalities were reported.

(Ron Verzuh is a writer, historian, and documentary filmmaker. He lived in Yellowknife in 1973 and travelled widely in the far north. Ron lives in Victoria. )

*