A merciless takedown of Mackenzie King

I was taken with Roy MacLaren’s new book about Mackenzie King and said as much in this review that turned up on May 13 in the Globe and Mail.

After talking privately with Adolf

Hitler in Berlin, Wailliam Lyon Mackenzie King concluded that the German Fuhrer

was a fellow mystic who spoke the truth when he insisted “that there would be

no war as far as Germany was concerned.” Hitler’s face, the Canadian prime

minister wrote in his diary, was “not that of a fiery, over-strained nature,

but of a calm, passive man, deeply and thoughtfully in earnest.… As I talked

with him I could not but think of Joan of Arc.”

That morning, as Mackenzie King had left

his Berlin hotel, he had sensed “the presence of God in all this,” guiding his

every step toward this meeting and “the day for which I was born.” June 29,

1937. Before he left Berlin, Mackenzie King wrote a note thanking Hitler for

giving him a silver-framed photo of himself – “a gift of which I am very

proud.” By this time, the Fuhrer had dispatched more than 4,000 innocents to

concentration camps and created laws turning German Jews into secoindnd-class

citizens.

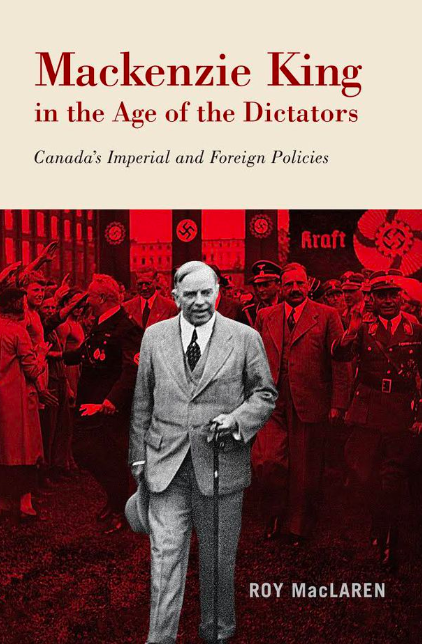

With Mackenzie King in the Age of

the Dictators, former diplomat and high commissioner Roy MacLaren eschews

biography to focus on the Canadian prime minister’s foreign-policy performance.

He delivers an exhaustively detailed, tightly controlled, yet merciless

takedown of Mackenzie King’s responses to both Benito Mussolini and Hitler.

If with Hitler we were not confronting

the most obscene tragedy of the 20th century – the industrialized slaughter of

more than six million Jews in the Holocaust – this encounter could be staged as

a farce in which a delusional bumpkin meets the worst tyrant of the age and

mistakes him for a holy man.

In March, 1938, after the Nazi

annexation of Austria, an unperturbed Mackenzie King wrote in his diary: “I am

convinced he [Hitler] is a spiritualist – that he has a vision to which he is

being true … that [his] Mother’s spirit is … his guide and no one who does not

understand this relationship – the worship of a highest purity in a mother –

can understand the power to be derived therefrom or the guidance … the world

will yet come to see a very great man – a mystic, in Hitler.”

Here, Mackenzie King was projecting what

Charlotte Gray has described as his “pathological obsession with his mother’s

memory” onto Hitler and fusing it with his ludicrously inflated fantasies of

his own significance. As he himself saw it, MacLaren writes, “he had played a

central, even divinely ordained role in keeping peace in Europe.”

As MacLaren makes clear, many Canadians

discerned the truth. Max Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook, made no rush to judgment

but, by 1934, according to one contemporary, he had become “solidly,

fanatically, anti-Hitler; refers to him as Al Capone and to the Nazis as

gangsters.” Around the time Mackenzie King was confiding to his diary, “I am

being made the instrument of God,” journalist Matthew Halton of The Toronto

Star described Hitler at a Berlin rally as a demonic orator who “turned his

hearers into maddening, moaning fanatics.” Over the course of a month in

Germany, Halton had “seen and studied the most fanatical, thorough-going and

savage philosophy of war ever imposed on any nation.”

When Mackenzie King hailed the Munich

Agreement, which ceded to Hitler much of Czechoslovakia (the Sudetenland),

Winnipeg journalist J.W. Dafoe – who had repeatedly warned against the Fuhrer’s

hate-filled rhetoric – wrote what MacLaren rightly describes as a “scathing

editorial” in which he denounced the appeasers for validating “the doctrine

that Germany can intervene for racial reasons for the ‘protection’ of Germans

on such grounds as she thinks proper in any country in the world.”

Ian Kershaw, the British biographer of

Hitler, summarized with the advantage of hindsight: “None but the most

hopelessly naïve, incurably optimistic or irredeemably stupid could have

imagined that the Sudetenland marked the limits of German ambitions to expand.”

Enter Mackenzie King.

Early on, Canadian diplomat Vincent

Massey deplored Mackenzie King’s “ostrich-like policy of not even wanting to

know what is going on.” He concluded that Mackenzie King combined an

anti-British bias with an extreme egotism, and after Kristallnacht, when Nazi

thugs went on a racist rampage and incarcerated 30,000 Jews, Massey wrote to

Mackenzie King that “the anti-Jewish orgy in Germany is not making [British

prime minister Neville] Chamberlain’s policy of ‘appeasement’ any easier.”

Mackenzie King agreed that “the post-Munich developments have made appeasement

difficult and positive friendship [with Hitler] for the moment out of the

question. That is no reason, however, why the effort should be abandoned.”

Unbelievable.

This book assumes a familiarity with the

history of Europe in the 1930s. It is a tour-de-force indictment of Mackenzie

King and, by implication, the political system that made him the

longest-serving prime minister in Canadian history. For those concerned about

the contemporary rise of fascism and neo-Nazism around the

world, Mackenzie King in the Age of the Dictators is ominous and

terrifying.

In September, Ken McGoogan will

publish Flight of the Highlanders: The Making of Canada.